Venous TOS

“You have a career-ending injury.”

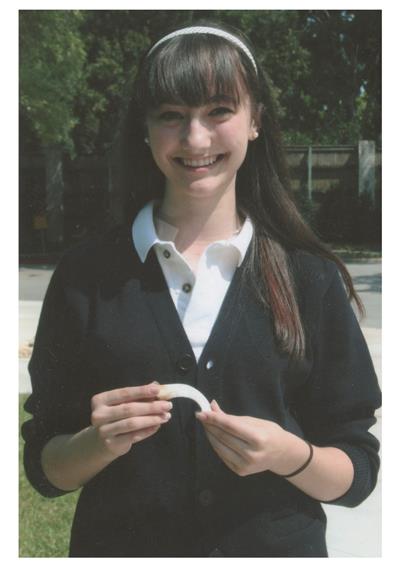

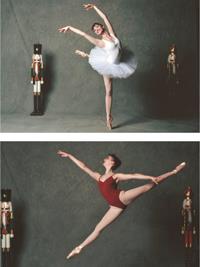

Kathleen McClure remembers those words as a terminal sentence to her promising ballet career. Just 16 years old, Kathleen had been enrolled in dance classes since the age of two. Determined to become a professional dancer, she began spending hours a day at a prominent ballet academy in Houston while still a youngster.

“She would go to an academic prep school in the morning and then run to the ballet academy and practice four to six hours a day during the week, and then again all day on Saturday,” says her mother, Judy. “She just couldn’t get enough of it. She loved dancing.”

The hard work and passion for ballet started to pay off. At 16, Kathleen was headed for the “summer of her dreams” in 2008 when she auditioned among hundreds of hopefuls and was accepted to attend summer programs with the prestigious School of American Ballet in New York City and the Royal Ballet School of London. “I was so excited to have those opportunities,” says Kathleen. “I just couldn’t wait for the summer to begin.”

But during final exams at the end of the school year, Kathleen woke up in the middle of the night with chest pain and tingling in one of her arms. “It hurt so bad, I didn’t think I could make it down the stairs,” she recalls. “By morning, my arm was swollen and I could barely write anything.”

Still, Kathleen went to school that morning and then to the ballet academy. Her instructors were startled at the size of her arm and told Kathleen’s mother to take her to an orthopedist as soon as possible. “I remember they did several tests after which we were told that Kathleen had a blood clot blocking her subclavian vein and three more clots in her lungs,” says Judy. “It took our breath away.”

Kathleen was taken by ambulance to a nearby hospital and then transferred to a second hospital. “Missing out on the summer programs was devastating, but I was in denial about the fact that my ballet career could be over,” she says. “I just couldn’t bring myself to believe what the doctors were saying because ballet was such a huge part of my life. I couldn’t imagine my life without dance.”

Doctors tried a clot-busting procedure called thrombolysis, but because of delays in diagnosing her condition, the drugs were ineffective. As her family despaired and considered surgery as a way to partially relieve the symptoms, Kathleen’s father turned on the television to watch the 2008 College World Series. It was an amazing twist of fate. “There on the television was an announcer talking about Colin Bates, a North Carolina pitcher who had undergone thoracic outlet decompression surgery after a blood clot was found in his right shoulder,” says Judy. “He was diagnosed with Paget-Schroetter Syndrome, or what is called venous TOS. We all looked at each other and said ‘that’s exactly what happened to Kathleen.’”

“That night, I looked him up on Facebook and e-mailed him,” says Kathleen. “The next morning, he wrote back in detail about his surgery and recommended his physician, Robert Thompson, MD, at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.”

“Kathleen indeed had venous TOS, which also is sometimes called ‘effort thrombosis’ because it is caused by a blood clot after heavy exercise or strenuous arm movements,” says Dr. Thompson, a board-certified vascular surgeon and the director of the Washington University Center for Thoracic Outlet Syndrome at Barnes-Jewish Hospital. “The chronic action of overhead movements, such as in pitching or ballet, can result in pinching of the subclavian vein and further narrowing from scar tissue, which then causes a blood clot to form.”

The Washington University Center for Thoracic Outlet Syndrome at Barnes-Jewish Hospital cares for more patients with TOS than any other place in the country. Currently, the Center is leading an effort to establish a national consortium and patient registry, to advance clinical trials and research into TOS and, it is hoped, identify better diagnostic tools and treatment options.

Within a week of her diagnosis, Kathleen underwent venous thoracic outlet decompression surgery by Dr. Thompson in St. Louis. A complex procedure, the surgery involves the removal of the anterior and middle scalene muscles, the subclavius muscle and costoclavicular ligament, and the entire first rib. Scar tissue is then removed from around the subclavian vein, and when necessary, the subclavian vein is repaired with a vein patch or a bypass graft. Recovery, which includes physical therapy, usually takes several months.

On August 20, just six weeks after her surgery, Kathleen was back at the ballet academy. “The pain following the surgery was bad, I’ll be honest with that,” says Kathleen. “But I was determined to recover, so I did all of the rehabilitation exercises religiously. I wanted to regain my muscle strength and range of motion as soon as possible.” She was helped by Matt Driskill and the team of physical therapists at The Rehabilitation Institute of St. Louis, who have acquired an extraordinary level of experience and expertise in caring for patients with TOS.

Kathleen’s recovery was an outstanding success. One year after undergoing surgery, Kathleen was headed to Switzerland, accepted as one of only a handful of students to receive a two-year scholarship to study at the prestigious Ecole-Atelier Rudra Bejart in Lausanne, Switzerland. She also was re-accepted to the School of American Ballet in New York for a six-week program in the summer of 2009. “We were told she would never have full use of her arm prior to her surgery,” says Judy tearfully. “Now, when I watch her dance, I think that the Lord has done amazing things in our lives.”

“It’s such a joyous thing, to be able to dance at all,” says Kathleen. “I had to wait a year to go the School of American Ballet, but now I know that my dance career is not over. I love Dr. Thompson and his team at Barnes-Jewish Hospital. He’s my hero.”

For more information on the Washington University Center for Thoracic Outlet Syndrome at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, please call Della Brink at (314) 362-7410.